Inkwell Readers Group - Forbidden Fruits

Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit by Jeanette Winterson.

Baring in mind Frank Kermode’s The Sense of An Ending from last month’s blog, these monthly book groups seem to be hurtling by as the months tumble, that invites that ‘extraordinary relation’ to time. Thankfully, the end is not immanent; we are still in our youthful beginnings as a book group (second month), and this time discussed Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit.

The book focuses on a young character, named Jeanette (I know, right), in a bildungsroman style coming-of-age novel of a girl who realises that she is not ‘normal’. To paraphrase that other famous bildungsroman, it could be titled ‘the portrait of a young girl as a lesbian in a pentecostal community’. Yes, the Pentecostal aspect of young Jeanette’s upbringing makes it a much more complicated matter and a much more interesting novel.

Jeanette is also adopted, which overlays the opening with a bittersweet irony on the matters of beginning. “Like most people I lived for a long time with my mother and father.” Indeed, that is one of the few occassions the father is actually mentioned, and that men are mentioned. Men feature rarely. In out book club’s partisan gender politics, we wanted a book by a female writer, and we managed to find a book that rarely mentions men at all.

But then there is also a greater irony to the question of fertility (indeed the opening chapter is called Genesis).

“She [her mother] had a mysterious attitude toward the begetting of children; it wasn’t that she couldn’t do it, more that she didn’t want to do it. She was very bitter about the virgin Mary getting there first. So she did the next best thing and around for a foundling. That was me.”

You’ve got to love that. Indeed, this irony and the humour persist throughout the novel.

Oranges are of course a key motif. Taken from Nell Gwynne’s epitaph, the famous mistress of King Charles II (also a famous ‘gay’ restoration character), if anything, the oranges, quite obviously seem to represent the dominant ideology. They are everywhere and offered everywhere, and often they are happily taken, without registering their symbolism (there is a poignant moment near the end between Jeanette and her mother about the significance, or rather, insignificance of oranges).

As a member of the pentecostal church, the church has profound impact on the upbringing and environment of Jeanette’s life. The book, as a result is framed Biblical headings. One of the most enduring messages about the book though is that stories are exactly that; stories, and guiding principles on which we base our narrative, and again Kermode chimes. As Jeanette realises the dominant clergy of the church, are not carrying a truthful word about the bible, but instead it is their interpretation which is all anything ever is. But It isn’t polemical; it does not denounce God, but those chapter headings (Exodus, Deuteronomy etc.) are further interpretations of God word. And this is Jeanette’s, as she uses the same biblical chapter headings to frame her narrative. We all have our own agenda .Despite being a completely different protagonist to Tony from Julian Barnes’ The Sense Of An Ending, as they concerned with interpretations of narrative. Indeed it is all subjective, and although it is largely autobiographical, it is still a narrative. As Kermode theorised, all our lives are.

I think the Inkwell Book Club is to become a justification of reading and why to read (inspired by Harold Bloom’s How To Read And Why, although he is much cleverer than I am to justify how), we should read OANTOF because it demonstrates how text, any text from the most religious to the most scientific, is just that – a text – a subjective construction of narrative. And as Religion, which gets a much worse press than Science, is portrayed as dogmatic and refutable, but so too sometimes is Science, just because it is the prevailing paradigm it doesn’t mean it isn’t a narrative. Science, as much as it relies on objective, logical reasoning, is it not to the mercy of the subjective account, given by the white-collar, usually male, white scientist, no?

We all need stories. Much like dear Nell Gwynn is portrayed as a ‘real-life Cinderella’, or should that be an ‘not-real-life normal person’? Some people just enjoy glossing it up a bit more. And making it funnier, much funnier. Much like…

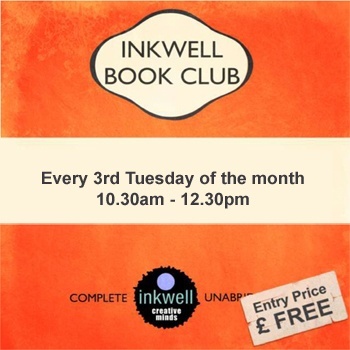

Next Time…

Howard Jacobson’s The Finkler Question (2011). Another Booker Prize winner, and shares slightly with OANTOF in that both author’s rejected the tag given to their novels by critics. Jacobson’s “comic novel” focuses on Julian Treslove and his two Jewish friends, Sam Finkler, an old school friend, and Libor Sevcik a former teacher, as he questions his identity, and Jewishness after being mugged. But is he Jewish enough for the attack to be classed as anti-semitic? Was it all a matter of fate?

As ever it is highly advised you read the book before attending. Books read available from all good bookstores, independent and high street. You could buy off amazon if you want, but why would you do that?